Kirksville is a rural town located in Northeast Missouri and is home to around 17,000 people, 600 of which are Congolese immigrants. Drawn to the promises of good education, safety, and community, people from the Congo began settling in Kirksville only a few years back. Explore some important milestones in Kirksville’s history below.

Immigration

Adair County looked very different prior to the establishment of the first white settlements in the 1830s and 1840s. Prior to this time, the Sauk (or Sac) Indians were the only inhabitants of this area of Northeast Missouri, though relations between the Native American group and the settlers were fairly peaceful for the first decade of settlement. However, the dogs were known to attack the settlers’ hog pens, causing tension between the two groups. This was deemed reason enough for the white settlers to drive the Indians off of their ancestral lands and even imprison them, resulting in their forced migration farther west.

Today, the inhabitants of Kirksville are still primarily white. However, recent migrations and demographic data show that the racial and ethnic makeup of Kirksville is by no means homogeneous, as the table below illustrates.

| Race/Ethnicity | 2000 | 2010 |

| White | 94.38% | 92.30% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.54% | 2.70% |

| Asian | 1.93% | 2.40% |

| African American | 1.73% | 2.20% |

| Pacific Islander | 0.04% | 0.10% |

| Other Races | 0.59% | 0.80% |

| Two or More Races | 1.07% | 2.00% |

The percentage of white residents has actually decreased between the years of 2000 and 2010, whereas the percentage of other races and ethnicities have increased across all categories. However, minority populations tend to be more spatially segregated from the majority population, and thus less noticeable to those who may not be looking close enough. While the Congolese population in Kirksville is by no means invisible, it is interesting to take this into consideration, especially when looking at how economic integration impacts overall community integration.

Industry

As the agriculture industry responds to the growing global need for food, more job opportunities are created in food processing and other nondurable manufacturing industries. Immigrants in the US often end up seeking out these jobs due to the language and cultural barriers they face when trying to find a way to utilize their skills with a limited English proficiency. Many of the Congolese people arrive in the US with advanced degrees, yet the majority of them work in the Kraft food factory and Farmlands food processing centers, where they are not able to use their knowledge or professional skills they have gained from their degrees back in the DR Congo. Getting re-certified in their area of expertise is often a time-consuming and difficult process, especially without the necessary English skills.

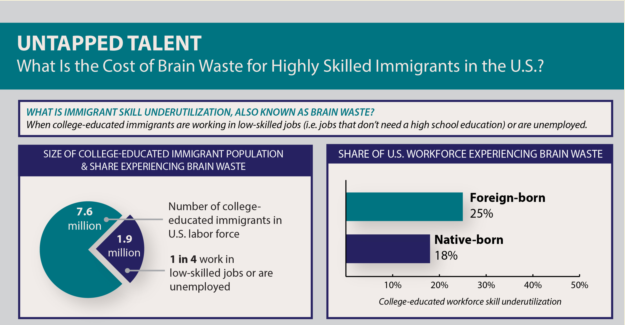

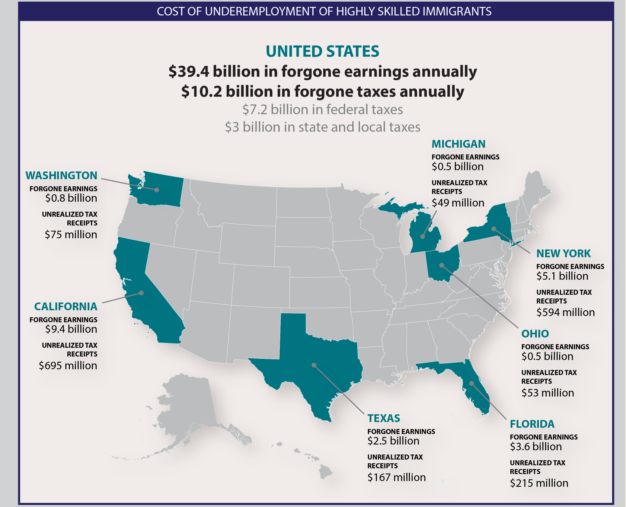

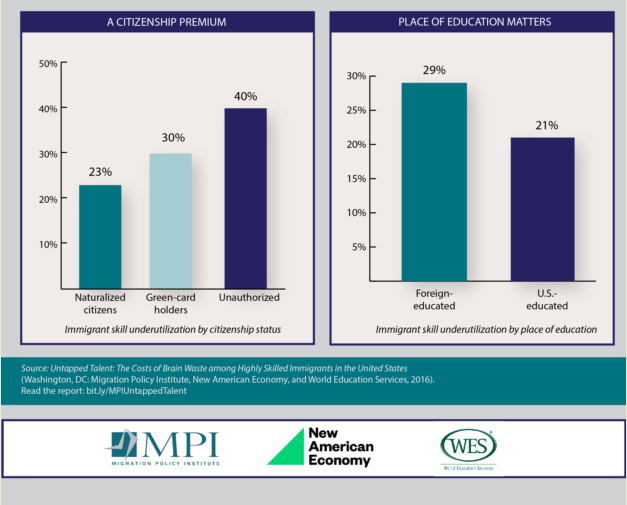

Many of us have heard of the concept of Brain Drain – – but not as much consideration has been given to its lesser-known counterpart, Brain Waste. Brain Waste is the phenomena where immigrants with higher education and specialized knowledge are forced to work lower-skilled jobs due to the insurmountable language barrier they face when moving to a different country. The burden of brain waste is certainly felt among the Congolese in Kirksville, but there is a significant amount of wasted brainpower in communities across the country. This directly translates to economic losses at the individual and institutional level. Brain waste claims $39 billion in lost wages and $10 billion in taxes, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

As mentioned above, this economic impact also has an effect on community integration. The schedules for the factory workers at Kraft and Farmlands are typically 12 hour shifts, with a few days on and a couple of days off. Some people work during the weekends. This can limit the interactions between factory workers and those who don’t work in the factories. This community isolation can be considered a latent effect of the brain waste problem that forces immigrant communities into lower-skilled jobs.

Education

The factory work schedules are also often times incompatible with school and class schedules. In order to make enough money to support themselves (and sometimes their families), many Congolese must work these jobs. Getting a better job necessitates a high level of proficiency in English, but are prevented from doing so due to the cost of these classes as well as their lack of available time.

For the children who have immigrated to Kirksville, the local school districts have been working to better accommodate their needs, however there is much work to be done. There is, after all, only one ESL teacher for the entire district, which isn’t conducive for the rapid language acquisition needed in order to participate fully in class. Unfortunately, the schools are reliant on government funding for school programs like ESL, and requests for aid usually don’t reach the school district until a year or a year and a half later, so they are constantly behind and trying to play catch-up. Groups like United Speakers and other volunteers have helped with tutoring for classes and English, but the district would greatly benefit from more funding and resources to meet the growing need for translation and ESL teachers.

Up next: Stories

1. Batalova, Jeanne, Michael Fix, and James D. Backmeier. “Untapped Talent: The Costs of Brain Waste among Highly Skilled Immigrants in the United States.” Migrationpolicy.org. December 2016. Accessed September 27, 2017. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/untapped-talent-costs-brain-waste-among-highly-skilled-immigrants-united-states.

2. Brown, Danielle. “Kirksville R-III Adapts in Order to Better Integrate Congolese Students.” Kirksville Daily Express, 14 December 2015. http://www.kirksvilledailyexpress.com/article/20151212/NEWS/151219704

3. Lichter, Daniel T. “Immigration and the New Racial Diversity in Rural America,” Rural Sociology, 77.1 (March 2012): 3–35, accessed 25 September 2017, https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1549-0831.2012.00070.x.

4. McHugh, Margie, Jeanne Batalova, and Madeleine Morawski. “Brain Waste in the Workforce: Select U.S. and State Characteristics of College-Educated Native-Born and Immigrant Adults.” Migrationpolicy.org. December 07, 2016. Accessed September 27, 2017. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/brain-waste-US-state-workforce-characteristics-college-educated-immigrants.

5. Missouri. Kirksville city. 2000 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital table. United States Census Bureau. American FactFinder. October 14, 2017. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=CF.

6. Missouri. Kirksville city. 2010 U.S. Census, population schedule. Digital table. United States Census Bureau. American FactFinder. October 14, 2017. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=CF.

7. Montgomery, Maxine. “Pioneer Days in Adair County,” Kirksville Daily Express, September 12, 1979, accessed September 25, 2017, http://www.adairchs.org/history/pioneer.htm.

8. “What Is the Cost of Brain Waste for Highly Skilled Immigrants in the U.S.?” Migrationpolicy.org. December 07, 2016. Accessed September 27, 2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/content/what-cost-brain-waste-highly-skilled-immigrants-us.