PREVIOUS: Land

Since its construction, the Parkway has become one of most visited national parks in the United States. From providing locals with construction jobs during the building phase to supplying an increasing number of hotel, restaurant, and retail jobs in order to keep up with tourist demands, the dialectic between WNC locals and the Office of the Blue Ridge Parkway is in part an economic one. However, economy is not the only thing that is effected by tourism. Local culture has served as a popular attraction for tourists along the Parkway.

Economy

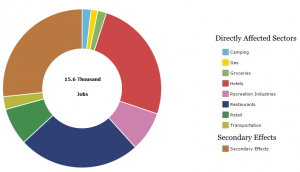

Job Sectors Affected by the Blue Ridge Parkway, 2016. Click on image to enlarge. Graph courtesy of the National Park Service. [3]

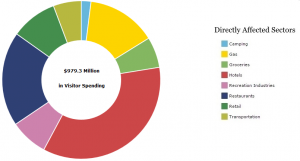

Visitor Spending in Local Economies from the Blue Ridge Parkway, 2016. Click on image to enlarge. Graph courtesy of the National Park Service. [5]

Culture

In an area that relies on tourism as one of its main industries, culture is undoubtedly influenced. The diverse city of Asheville is assuredly made even more diverse by the sundry assortment of visitors, but pro-Parkway leaders used stereotypes about locals in their fight to bring the Parkway to WNC. This is in part due to the popularity of these stereotypes about the “mountain folk.” The Asheville Citizen Times, a local newspaper, believed the BRP would bring “thousands of visitors” who would “bring to [locals’] doors a market for their labor, a market for the products of their little farms, a market for the various things which they would be able to make and sell.” [6] Even as the North Carolina route was being presented to the department of Interior, the idea of encountering “primitive mountain folk” who did not speak grammatically correct English was encouraged by the New York Times.[7]

Alleghany Jubilee. Photo Courtesy of http://alleghanyjubilee.com/.[8]

Tommy Jarrell and Fred Cockerham, Sugar Hill [11]

The Alleghany Jubilee is only one example of the celebration of traditional music along the Blue Ridge Parkway. The Parkway itself also boasts a Music center located in Galax, Virginia, only a few miles beyond the North Carolina state line. The music center hosts exhibits and live performances that “trace the diversity of American roots music to the region.”[12] In addition to honoring the musical heritage of the Blue Ridge Mountains, the BRP Music Center also encourages the creation of new (traditional style) music in the communities that “still maintains a wellspring of old-time, bluegrass, and mountain gospel sounds.” While located in Virginia, the center incorporates music from North Carolina, specifically those counties that hug the state line such as Alleghany, Surry, and Stokes. [13]

Image Courtesy of the Southern Highland Crafts Guild. [15]

UP NEXT: Tourism

Footnotes

[1] National Parks Service, Visitation historic and Top 10 Sites, accessed October 31, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/visitation-historic-and-top-10-sites-2014.pdf.

[2] Public Works Administration, “Shenandoah-Smoky Mountain Parkway and Stabilization Project:Proceedings of the Meetings Held in Baltimore, February 5,6,7, 1934,” Record Group 79 (National Park Service), Central Classified Files, 1933-49, Entry 18, “Records of Arno B. Cammerer, 1920-1940,” National Archives II, College Park, Maryland, 30-32, quoted in Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 82.

[3] National Park Service, “Total Jobs Contributed to Blue Ridge Parkway Economics, 2016,” chart, National Park Service, accessed November 22, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/socialscience/vse.htm.

[4] “More than Just a Road: Protecting Parkway Viewsheds,” Blue Ridge Parkway Directory and Travel Planner: Celebrating 75 Years, 61st Edition, Blue Ridge Parkway Association, 2010, Ephemera, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Asheville, North Carolina, 13.

[5] National Park Service, “Total Visitor Spending (Blue Ridge Parkway), 2016,” chart, National Park Service, accessed November 22, 2017, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/socialscience/vse.htm.

[6]“Locating the Scenic Parkway,” Asheville Citizen Times, March 25 1934, B2, quoted in Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super Scenic Motorway (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006,) 81.

[7] “New Scenic Ridge Road: Three States Combining with Government to Build Motor Way,” New York Times, February 11, 1934, section 20, p.8, quoted in Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super Scenic Motorway (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 83.

[8] Alleghany Jubilee Logo, digital image, Alleghany Jubilee, accessed November 9 , 2017, http://alleghanyjubilee.com/.

[9] Agnes Joines, 2003, interviewed by Philip E. Coyle, November 8, Sparta, North Carolina, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Asheville, North Carolina, 4.

[10] “Alleghany Jubilee – Sparta, North Carolina,” Alleghany Jubilee – Sparta, North Carolina, accessed November 09, 2017, http://alleghanyjubilee.com/.

[11] Tommy Jarrell and Fred “Sugar Hill,” Good Time Music, December 22, 2011, accessed November 9, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VVfYsQyihpQ?rel=0&w=280&h=157.

[12] “Blue Ridge Music Center,” Blue Ridge Music Center – Blue Ridge Parkway, http://www.blueridgeparkway.org/v.php?pg=120, accessed November 09, 2017.

[13] “Music of the Region,” Membership- Blue Ridge Music Center, http://www.blueridgemusiccenter.org/history.htm#, accessed November 01, 2017.

[14] Philis Alvic, Weavers of the Southern Highlands (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), 21.

[15] Folk Arts Center, digital image, Southern Highland Guild, accessed November 22, 2017, http://www.southernhighlandguild.org/retail-shops/folk-art-center/.

[16] “Constitution: Southern Mountain Handicraft Guild,” Southern Highland Handicraft Guild Archives, Montreat College, Black Mountain, North Carolina, quoted in Philis Alvic, Weavers of the Southern Highlands (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), 21.

[17] “Cultural Heritage,” Cultural Heritage – Blue Ridge Parkway, , accessed November 22, 2017, http://www.blueridgeparkway.org/v.php?pg=43.