PREVIOUS: Locals

The interaction between the North Carolina state government, the BRP, and locals who lived near or along the proposed Parkway route is one of opposition and compromise. In many cases, there were those, such as individuals in Ashe and Alleghany Counties, who did not wish to sell. Even after the Parkway had purchased the land necessary for the great scenic highway, they offered the option of land leases to local farmers. Scenic easements were another way the Parkway continued working with locals long after the BRP itself was built.

Buying and Selling

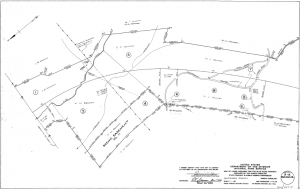

Right of Way map illustrating scenic easement and rerouting roads. Photo Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Headquarters.[2]

Ernest Whanger recalled such people in his memoir, remembering how they “received polite answers and courteous attention” but they “did not find a single land owner who thought we were making a reasonable offer. [3] In some cases the state would find reason to condemn the land and force the owner to sell. Such an option was considered for the Miller property when the Miller family refused to sell.[4] In an attempt to placate land owners, the BRP used a combination of scenic easements, fee simple (giving adjacent land owners full rights and control over their land) , and buying land. As early as June 1935, North Carolina had acquired all the necessary land rights for section 2A (around Alleghany and Surry Counties) of the Parkway, although they continued to have issues with surrounding land owners cutting timber in areas that violated scenic easement agreements.[5] Issues of land most certainly shaped local perception of the Parkway, causing plenty of disagreements and disputes and was riddled with violations by those who resented some of the constrictions placed on them by the Parks Service, but in the end the the Parkway acquired the necessary lands and the project moved forward, much to the dismay of some locals and to the joy of others.

Land Leasing and Scenic Easements

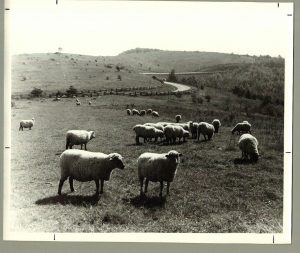

Land Leases and Scenic Easements gave locals a unique chance to interact with the BRP by allowing them to raise crops or graze animals within view of the Parkway. Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives. [8]

UP NEXT: Economy and Culture

Footnotes

[1] Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 123-124.

[2] United States Department of Interior, National Parks Service, Maps of Lands Acquired for the Blue Ridge Parkway: Alleghany and Wilkes Counties from U.S. Route No. 21 to Air Bellows Gap, ROW Maps, Section 2-B, Blue Ridge Parkway Headquarters, 6.

[3] Ernest G. Whanger, Memorandum: 1968 FY Inholding Program, September 9, 1966, Record Group 7: Records of the Resient Landscape Architect, Series 22: Acquisition of Lands- General Correspondence Files 1966-1973, Box 22, Folder 28, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Asheville, NC.

[4] Summary of Accepted Options (July- September FY 67), 1966, Record Group 7: Records of the Resient Landscape Architect, Series 22: Acquisition of Lands- General Correspondence Files 1966-1973, Box 22, Folder 28, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Asheville, NC.

[5] Stanley W. Abbott, Superintendent’s Annual Reports Blue Ridge Parkway, 1934-1946, Superintendent’s Annual Reports, Asheville, North Carolina, 10.

[6] Office of the Blue Ridge Parkway, Blue Ridge Parkway News 1, no. 2, December 1937, Blue Ridge Parkway Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[7] Blue Ridge Parkway News 2, no. 6, June 1939.

[8] Sheep in Field, Record Group 11, Box 11, Folder 42, Blue Ridge Parkway Photograph Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

[9] Regulations and Procedure to Govern the Acquisition of Rights-of-Ways for National Parkways, February 8, 1935, 3, quoted in “Lesson Plan,” Appalachian State College, Special Collections, accessed November 25, 2017, https://history.appstate.edu/sites/history.appstate.edu/files/neh/resources/ScenicEasementsandLandUse.pdf, 10.