WHO ARE LATINOS?

The term Latino is widely discussed among scholars, activists, and advocates because of its breadth and ambiguity. That being said, we are not interested in redefining the term, but rather we wish to clarify our use of it throughout this study. The term Latino has been in use since the mid 1940’s as a way to describe individuals in the United States who have cultural or historical ties to Latin America, much in the same way that Hispanic or Spanish refers to people with cultural or historical ties to Spain. The term Latino is one of many Pan-ethnic and cultural labels that is not intended to define a person’s race, ethnicity, country of origin, legal status, or citizenship, but instead reflects a social group within the United States.1

MEXICAN HISTORY

Throughout this study, the term Mexican and Latino is used interchangeably to discuss the migration history and culture of individuals and families specific from Mexico. Individuals of Mexican descent born in the United States may also identify as Chicano. The term Chicano is used as a sense of hope and pride in “embracing the political consciousness of the Mexicans’ history in the United States.”2 It also represents larger movement fighting and advocating for the civil and political rights and equality of Mexicans and Latino throughout The United States. Many sources throughout this study are a reflection of either the Latino, largely Mexican, population in Stevens County or of the larger Chicano movement in the Midwest and United States.

The political and topographical history between Mexico and what is now the United States is one that is all too often forgotten, ignored, or in most cases simply, unknown. Before 1818, Spain claimed all the lands west of the Continental Divide, but following the Transcontinental Treaty in 1819, Mexico’s gain of independence in 1821, and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, ending the Mexican-American war,3 the United States’ expansion West had reduced Spain’s original land holdings in North America by over 55%, an area of approximately 970,000 sq. miles.4 As is the case with most political land transfers, native populations are often displaced and villainized, as was and still remains to be the case for those persons of Spanish and/or Mestizo decent labeled or identifying as Mexicans.

Below is a slideshow that shows the progression of change in seven distinct periods.

MEXICAN MIGRATION

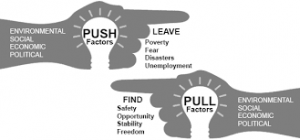

Factors of Immigration

There are often many, very simplified explanations of the factors that influence the migration of people, goods, and industry. These factors have long term implications on the perceptions of the migration across the U.S./Mexican border as well as every other community that migrates from one area to another. This image clearly outlines a few of the individual factors that are vital to the migration process. Continue throughout the site to see the ways that war, industry, economics and globalization lead people toward a better land.

Waves of Immigration

Although Mexican migration to and from the United States has remained a constant throughout the nations’ history, the specific pattern of migration to the United States can be broken into four distinct waves.

The first being during and after the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Even before the Mexican Revolution broke into violent war, refugees and political exiles fled across the border into the neighboring United States. With increased violence, Mexico experienced a surge of migration from rural areas into larger cities or familiar places in the US. As a result of this, the Mexican migration in the U.S. rose sharply and documented migrants grew from 20,000 in the 1910s to 50,000-100,000 individuals each year during the 1920s. Throughout this migration pattern, women and children were the most vulnerable, because many men were fighting the war. Because of this imbalance, migrants often arrived in large numbers with very few material goods and without extensive work experience outside of the home. As families continued to reconnect and grow in the United States throughout the span of the war and after, the population of Mexican and Mexican American communities rose significantly north of the border.5

The second wave was during World War II called the Bracero Program. This program began in 1942 as there was a need for farmhands in The US Southwest when American men were sent to war through the draft program. A surge in landownership left those with excess land and consistently high demands seeking new help. The Bracero program brought with it much discussion over workers rights, fair pay, length of work, and contract loyalty which made it a key factor in the sudden growth of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States Southwest. This was a larger movement that some scholars recognize as active today. Even after World War Two ended in 1945, the Bracero Program did not end until after harvest in 1965 and Mexican employment on the border hardly decreased.

The third wave of Mexican immigration to the United States was after the mid 1960’s at the height of the Border Industrialization Program. With this program, the United States allowed and financed American corporations to send domestic materials for manufacturing in fabricas, factories, in Mexico. This was attractive to many large toy, car, and construction companies in order to manufacture products without the need to abide by regulations of the United States Federal Government or Environmental Protection Agency.6

Lastly the fourth wave came after Mexico joined the U.S. and Canada in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. Through NAFTA, both nations hoped that increased trade and industry would boost Mexico’s economy and lead to higher employment and pay rates, resulting in decreased migration numbers out of Mexico. However, the predicted growth of the Mexican economy due to the implementation of NAFTA, did not materialize.7 Not only that, but “the flow actually increased, mainly during the first 15 years with a combination of increased demand-pull pressures in the US, especially during the job booms of the late 1980s and late 1990s, and increased supply-push pressure in Mexico.”8

The North American Free Trade Agreement and its creation of a temporary professional visa,the “TN” visa, and its accompanying dependent/spousal visa, the “TD” visa, have had a significant impact on Mexican migration patterns in Stevens County, as many local corporations dependent on the hiring of Mexican veterinaries, agronomists, and engineers.

Image Bibliography

- “Globe of Latin America.” Map. Wikipedia.

- “Viceroyalty of the New Spain 1819 (without Philippines).” Map. In By Giggette [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.

- “Viceroyalty of the New Spain 1800 (without Philippines).” Map. In By Giggette [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons.

- “Territorial evolution of Mexico.” Wikipedia. November 07, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Territorial_evolution_of_Mexico. (Accessed November 21, 2017).

“Carecen 2004.” SPARCinLA. http://sparcinla.org/carecen-2004/. (Accessed November 21, 2017).

- “Mexican Revolution Refugees,” photograph, 191u, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, texashistory.unt.edu; crediting El Paso Public Library: https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth63521/. (Accessed December 6, 2017)

- MexicaliBraceros,1954. Los Angeles Times photographic archive, UCLA Library (Los Angeles Times) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. In Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AMexicaliBraceros%2C1954.jpg. (Accessed November 21, 2017). - “Is the NAFTA TN Visa Right for Me? U.S. Immigration.” Immigration Attorney & VISA Law Office in Los Angeles. December 17, 2014. http://www.jcsimmigration.com/nafta-tn-visa-right-for-me/. (Accessed November 23, 2017).

Bibliography

- Manolis, Argie. “The Latinos in Morris – ESL training.” Lecture, Morris, 2017.

- Gallardo, Miguel E. “Chicano.” Encyclopædia Britannica. March 24, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chicano. (Accessed November 23, 2017).

- “Territorial evolution of Mexico.” Wikipedia. November 07, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Territorial_evolution_of_Mexico. (Accessed November 21, 2017).

- Quijada, Pedro. “Lecture.” January 26, 2016.

- “Washington State University.” Spring 2015 Mexico Immigration Causes and Consequences Comments. https://history.libraries.wsu.edu/spring2015/2015/01/19/usmexico-immigration-policies/. (Accessed November 23, 2017).

- Quijada, Pedro. “Lecture.” February 16, 2016.

- Verea, Mónica. “Immigration Trends After 20 Years of NAFTA.” NORTEAMÉRICA, 2014: 110

- Kovtun, Iuliia, Nataliia Stolyarova, Samuele Gherardi, and Matteo Cappella. “The NAFTA and the migration issue.” Universita di Macerata, n.d.: 1