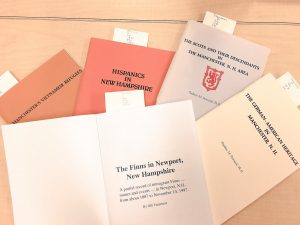

A visit to the Keene State College archives revealed a lot about different migrant and immigrant groups that came to New Hampshire that I had no idea even existed in New Hampshire. These groups that I was personally unaware of were the Finnish, Vietnamese and the Lebanese migrant and immigrant groups. The groups that I was aware of are the Scots-Irish, Irish, French Canadian, German, and the Hispanic communities. It was an eye opener on what groups have lived in New Hampshire that I never even heard of. On this initial visit to the archives none of the books focused on Keene, New Hampshire, but rather on Manchester, New Hampshire’s largest city. However there was one noticeable exception to that, and that was the Finnish community of Newport, New Hampshire.

A book called The Finns in Newport, NH by Olli Turpeinen discusses the Finnish community that formed in Newport. The Finns did not settle in New Hampshire largest city of Manchester, despite it being the center of New Hampshire immigration. This was because of other ethnic groups such as the Irish and French Canadians already living in the city. They moved to Newport in the 1880’s because of the various job opportunities that were closed off to them. Finns went to Newport for employment in a town that was willing to hire them. The community continued to grow into the twentieth century, and immigration and migration continued throughout New Hampshire.

Manchester, New Hampshire was the top immigration destination for many arriving in the state. As stated earlier numerous migrant and immigrant groups made their home in Manchester. Another group that was fascinating was the Lebanese community. This group arrived in the early 20th century, and managed to open several small businesses according to Thaddeus M. Piotrowski’s The Lebanese Community of Manchester. At the moment I don’t know much more about this community but, I’m interested in doing a project either on the Lebanese in Manchester or the Finns in Newport. It was interesting to explore the archives as I truly discovered communities I did not know existed. All information came from the books The Finns in Newport, NH Olli Turpeinen and Thaddeus M. Piotrowski’s The Lebanese Community of Manchester.

Patrick Driscoll, my partner in this COPLAC course, and I visited the Keene State College Archives to begin our research on migration history in New Hampshire. It was not the first time we had been here together and our previous experience conducting archival work certainly contributed to the ease of use we had in the facility this time around. We were able to quickly find, not without the help of our lovely archivists, several records of migration populations in New Hampshire. What we discovered were books. Most of these books come from a collection written by Thaddeus M. Piotrowski who spent what seems to be many years compiling information about various immigrant populations existing in New Hampshire, and specifically in the Manchester area, throughout history. Piotrowski produced individual books about each migrant group, went into detail about their histories, cultures, successes and setbacks living in the region, and much more. The groups were: Hispanics in New Hampshire, mostly lured here by an industrialized Granite State’s mills and textiles; Scots and their descendants in Londonderry New Hampshire; German-American groups and their heritage in New Hampshire; Vietnamese refugees of New Hampshire; the Finnish in Newport, New Hampshire, and the Lebanese population in New Hampshire.

Patrick Driscoll, my partner in this COPLAC course, and I visited the Keene State College Archives to begin our research on migration history in New Hampshire. It was not the first time we had been here together and our previous experience conducting archival work certainly contributed to the ease of use we had in the facility this time around. We were able to quickly find, not without the help of our lovely archivists, several records of migration populations in New Hampshire. What we discovered were books. Most of these books come from a collection written by Thaddeus M. Piotrowski who spent what seems to be many years compiling information about various immigrant populations existing in New Hampshire, and specifically in the Manchester area, throughout history. Piotrowski produced individual books about each migrant group, went into detail about their histories, cultures, successes and setbacks living in the region, and much more. The groups were: Hispanics in New Hampshire, mostly lured here by an industrialized Granite State’s mills and textiles; Scots and their descendants in Londonderry New Hampshire; German-American groups and their heritage in New Hampshire; Vietnamese refugees of New Hampshire; the Finnish in Newport, New Hampshire, and the Lebanese population in New Hampshire.